Unit 8+9

Molecular Geometry and Polarity

Lattice Energy

Lattice energy is the change in energy when an ionic solid goes to its ions in their gaseous states.

Lattice energy increases with:

- Increasing charge of the ions

- Decreasing size of ions

It is very difficult to directly measure lattice energies for ionic substances, so they are usually theoretically calculated from other data. The other changes add up to the full change from gaseous ions to ionic solid, and their energies can be added together (kind of like Hess's Law).

Types of Bonds

There are three basic types of bonds:

- Ionic

- Electrostatic attraction between ions.

- Form between a cation and an anion, usually a metal and a nonmetal.

- Covalent

- Sharing of electrons.

- Form between two nonmetals.

- Metallic

- Atoms attracted to electrons which are free to move through the metal.

- Form between metals.

Lewis Dot Structures

Basics

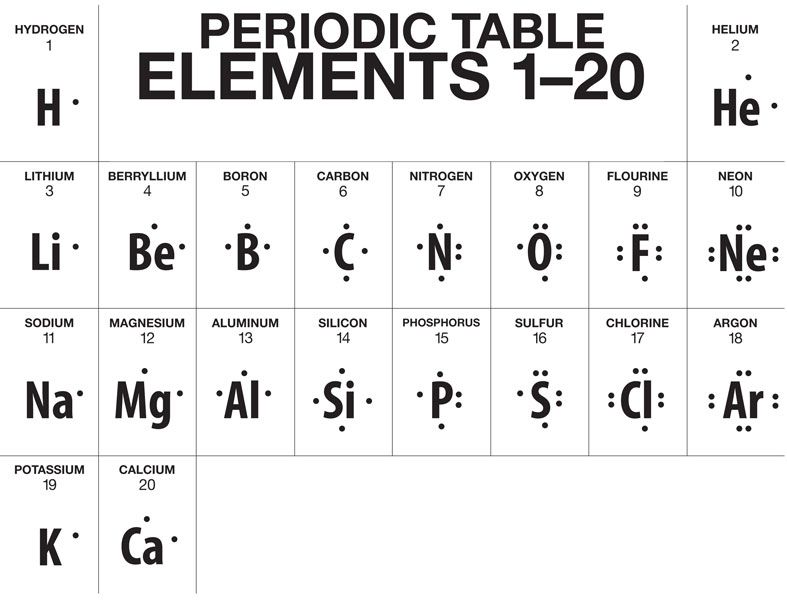

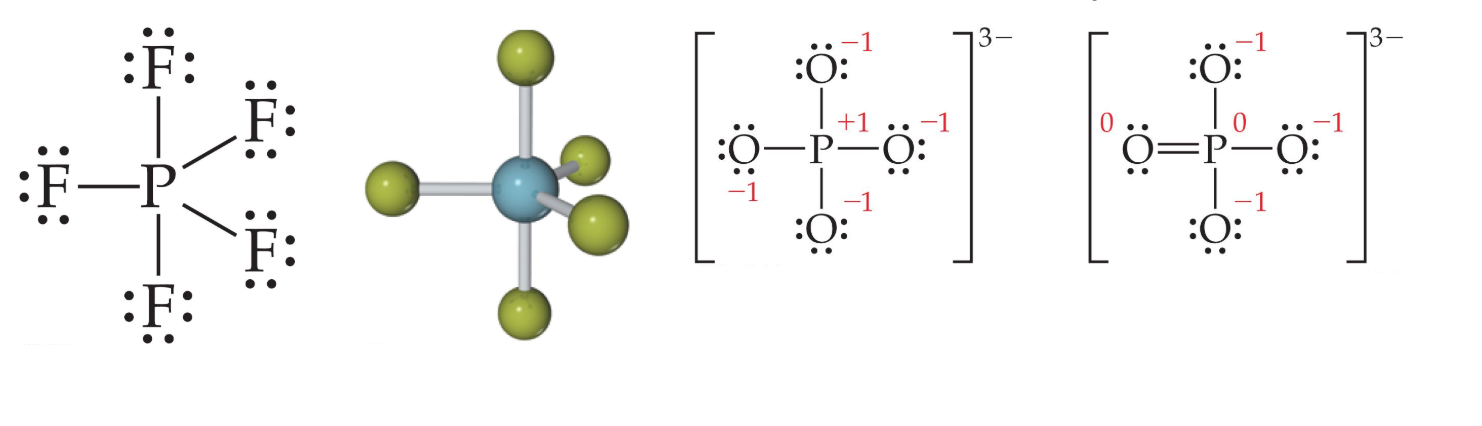

Lewis dot structures look like this:

The dots represent valence electrons. Notice that four electrons must be present before subsequent electrons are paired.

Covalent bonds and Lewis dot diagrams

Sharing electrons to make covalent bonds can be demonstrated using Lewis structures.

The octet rule says that each electron should have a total of eight valence electrons (or zero, since the next level of 8 electrons becomes valence). The exception to this rule is hydrogen, which only needs two valence electrons.

How to draw a Lewis structure for covalent molecules:

Example:

Sum the valence electrons from all atoms, taking into account overall charge.

has 5 electrons, and each has 7 electrons, so there are 26 total electrons.Arrange the symbols for atoms correctly, and connect the atoms.

The central atom is the atom of lowest affinity for electrons, since it will be donating the most electrons. Often, but not always, this is the first element in the formula, but it's never .

In this case, the central atom will be , and the three atoms will each be attached to the central atom.

Each bond is two electrons, so there are electrons left.

Complete octets around all atoms bonded to the central atom.

Each atom gets 6 electrons. Therefore, there are electrons left.

Place any leftover electrons on the central atom.

There are two electrons left, so we place both electrons in a pair on . It then has all eight electrons, and we've used up all 26 electrons.

If there are not enough electrons to give the central atom an octet, try multiple bonds.

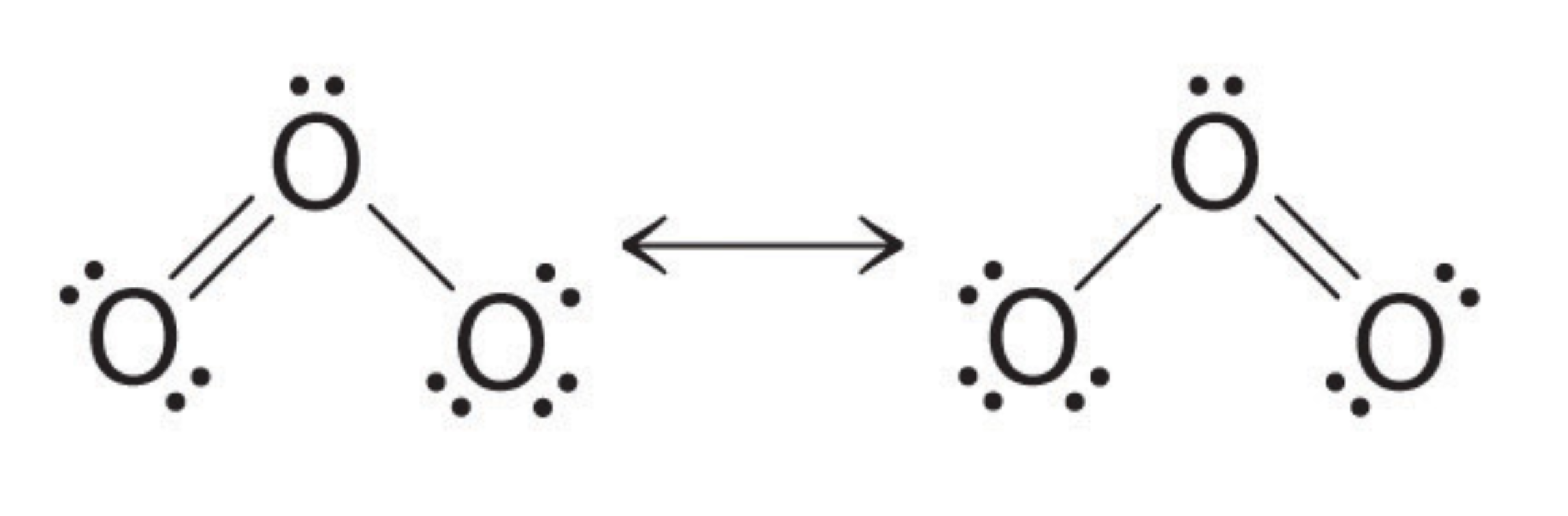

Resonance Structures

For some molecules we use multiple structures, called resonance structures, to accurately depict the bonds. The ↔ symbol is used to indicate multiple resonance structures. For example, ozone:

The electrons that are shared by multiple atoms are called delocalized electrons, whereas normally the electrons are localized electrons.

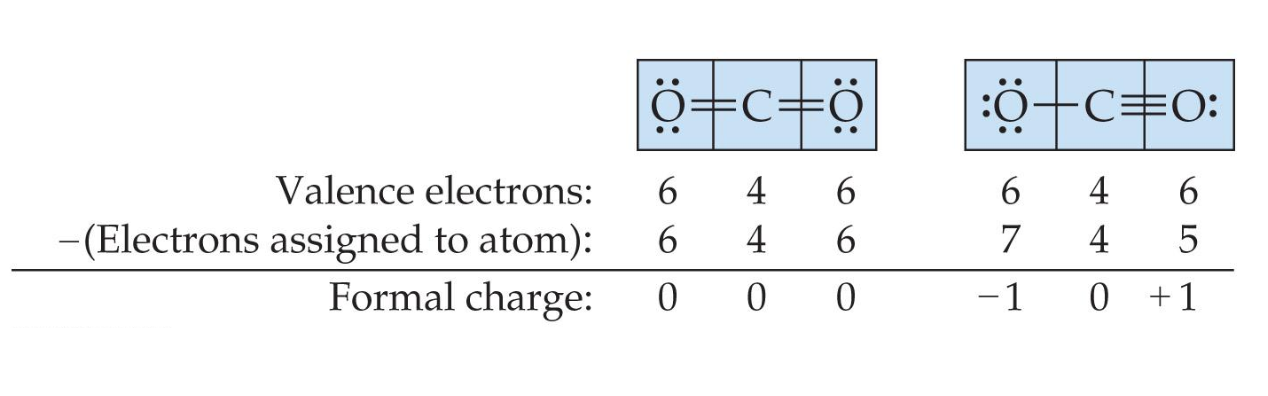

In order to determine which resonance structures are more dominant, we calculate formal charge. Formal charge is the charge an atom would have if all of the electrons in a covalent bond were shared equally.

The dominant resonance structure:

- is the one in which atoms have formal charges closest to zero.

- puts a negative formal charge on the most electronegative atom, if needed.

Exceptions

Odd number of electrons

Though relatively rare and usually quite unstable and reactive, there are ions and molecules with an odd number of electrons. For example:

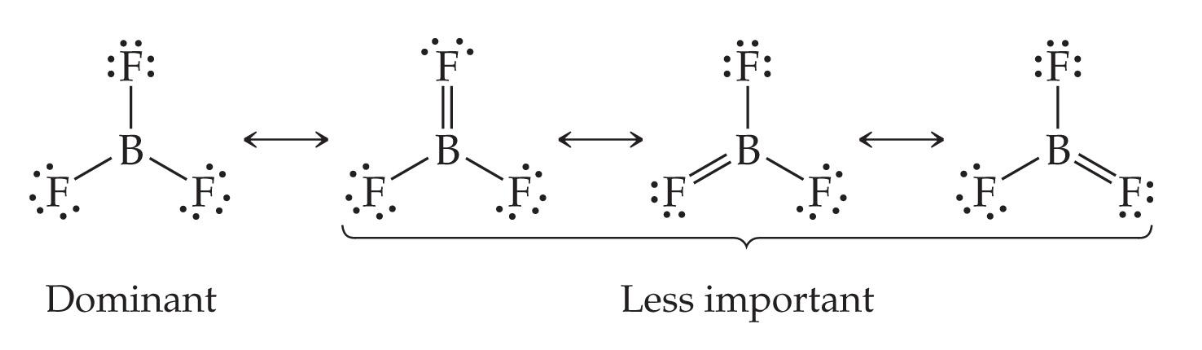

Fewer than eight electrons

and can make stable compounds with fewer than eight electrons.

Here, fluorine is highly electronegative, so it does not want to give any electrons to boron.

More than eight electrons

When an element is in period 3 or below in the periodic table, it can use d-orbitals to make more than four bonds.

This often happens when outer atoms are highly electronegative.

One would actually have to draw four resonance structures with five bonds on the phosphorus atom, making four structures similar to the rightmost structure above. This is because there are four ways to place the double bond.

Tricks for drawing Lewis structures

HONC 🦆

Hydrogen, Oxygen, Nitrogen, and Carbon usually make 1, 2, 3, and 4 bonds, respectively.

Oxidation numbers

You can use oxidation numbers to predict whether a molecule will have an extended octet.

For example, in O's oxidation number is -2. Since the overall charge of the molecule should 3-, the charge of P is +5. Therefore, P should give away 5 electrons and will have 5 covalent bonds.

Molecular Geometry

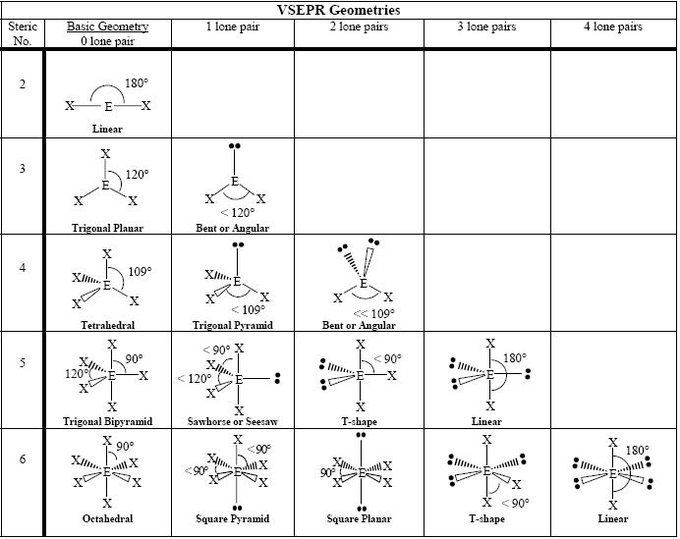

You can figure out the molecular geometry of a molecule using its Lewis dot structure.

Every molecule adopts the shape that minimizes the electron pair repulsions between electron domains (the region around the central atom in which electrons are most likely to be found; either one or multiple bonds or an electron pair).

They have names, which can be fairly easily memorized based on the shapes of the bonds:

Notes on molecular geometry

- When there are 5 electron domains, the 3 electrons around the equator (instead of the 2 poles) are removed first. This is because the equatorial electrons have less repulsion, and lone pairs create more repulsion than bonds.

- In some situations (such as the second example for 3 electron domains above), the angles may become lesser when bonds are replaced with lone pairs. This is also because lone pairs create more repulsion than bonds and take up more room than bonds, so they push on the remaining bonds.

Polarity

The molecular geometry of a molecule can be used to determine whether it is polar, meaning that they have an unequal distribution of charge around the molecule.

A polar bond is a bond where the difference in electronegativities between the atoms is between 0.4 and 1.7 (less than this is nonpolar, more than this is ionic).

Determining polarity

To determine whether a molecule is polar, imagine its molecular geometry.

If a molecule has polar bonds and/or lone pairs that are not placed symmetrically, then some sides of the molecule are differently charged than others, and the molecule is polar.

Dipole moment

The polarity of a molecule can be quantified as its dipole moment, or D. A higher dipole moment means more polar.

Valence-Bond Theory

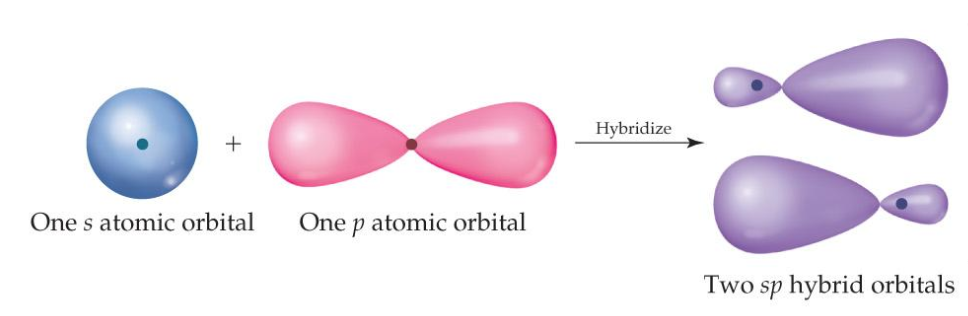

The problem: Elements such as carbon form tetrahedral shapes by bonding their valence electrons. How is this possible when combining the circular electron orbital from 2s and the three dumbbell-shaped electron orbitals from 2p?

This uses hybrid orbitals, which form by "mixing" atomic orbitals to create new orbitals of equal energy, called degenerate orbitals.

Hybrid orbitals example

Boron's electrons are promoted to higher shells, and then hybridized into hybrid sp orbitals.

The sp orbitals created look like this:

Since three orbitals were involved in creating boron's sp orbitals (2s, and two of the three 2p orbitals), there will also be three sp orbitals created. This allows boron to form three covalent bonds, giving it a trigonal planar shape.

This sp orbital is called because it came from one s orbital and two p orbitals.

Sigma and pi bonds

Double and triple bonds require a different type of bond.

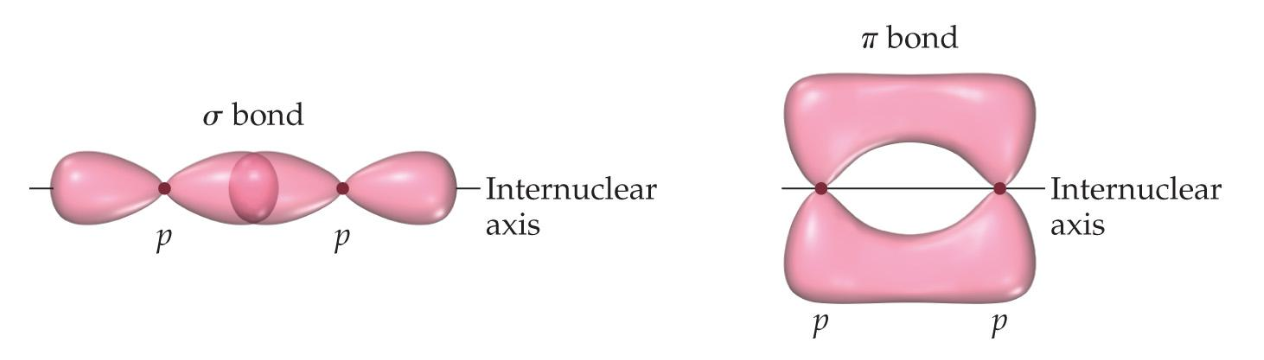

- Sigma () bonds have head-to-head overlap

- Pi () bonds have side-to-side overlap, which allows them to fit around existing sigma bonds

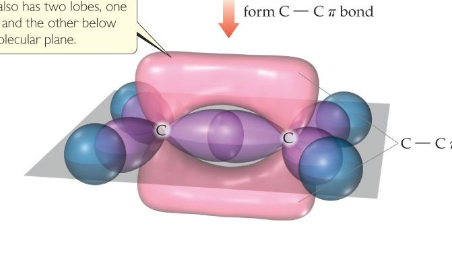

If you need to create a double bond, you can use one sigma bond and one pi bond. You couldn't use two sigma bonds, because they would take up the same space. However, you can use one of each, because they occupy different spaces, as shown below with two carbon atoms:

You can even create a triple bond using one sigma bond and two pi bonds, since the pi bonds' shape allows them not to overlap:

Electronegativity

Electronegativity is the ability of an atom in a molecule to attract electrons to itself. On the periodic table, electronegativity generally increases from left to right and bottom to top.

Electronegativity and covalent bonds

When two atoms share electrons unequally, a polar covalent bond results.

Electrons tend to spend more time around the more electronegative atom. The result is a partial negative charge (not a complete transfer of charge). It is represented by ("partially positive") or ("partially negative").

A molecule is dipole if it has two significantly differently charged poles, due to significant differences in electronegativity.

Bond order

Bond order is the number of bonds between a pair of atoms. It's proportional to two important properties:

- Bond strength (energy required to break a bond)

- Bond length (distance between atoms)

Essentially, higher bond order = shorter bond length (more bonds = each bond is shorter), and higher bond order = stronger bond.

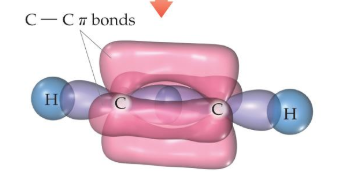

Bond energy curve

The AP test likes to show graphs like this:

The optimal spot (where there is the lowest energy) is the bottom of the curve.