Unit 7

Periodic Properties

Trends at a Glance

Property

Atomic Radius

The distance between the nucleus and the outermost electron.

Effective Nuclear Charge

The attractive charge of nuclear protons acting on valence electrons.

Ionization Energy

The energy required to remove an electron from an atom in the gas phase.

Electron Affinity

The energy change accompanying the addition of an electron to a gaseous atom.

Across a Period

Decreases

More protons are added to the nucleus, which pull the electrons in with more force.

Increases

More protons are added to the nucleus, while the number of repelling electrons in inner shells stays the same.

Increases

The electrons are held more tightly (see effective nuclear charge), so they're harder to remove.

Increases

Effective nuclear charge increases, which increases pull towards electrons.

Down a Group

Increases

New energy levels are added, which are farther from the nucleus.

Decreases slightly

Although nuclear charge increases down a group, shielding from added electrons more than counters this effect.

Decreases

Valence electrons are farther away from the nucleus, so they're less tightly held.

Decreases

The electron cloud becomes larger, so new electrons are further from the nucleus and therefore pulled with less force.

Atomic Radius

Atomic radius is the distance between the nucleus and the farthest valence electron of an atom.

As expected, atoms with the largest radius are found at the bottom of the periodic table, since these atoms have the most electrons in their electron cloud.

However, the atomic radius decreases as one moves across a period. This is because there are more protons in the nucleus, which pull the electron cloud towards the nucleus more tightly.

Ionic Radius

Ionic radius is the same as atomic radius, but for ions. Its trends are the same as for atomic radius.

Anions are larger than the atoms from which they come, because there are more electrons and the same number of protons.

Effective Nuclear Charge

Effective Nuclear Energy, or . It can be approximated by subtracting the number of "core" electrons (not on the outermost principal quantum number) from the total number of protons. This simulates removing the effect of the shielding electrons, which are electrons between the nucleus and the valence electrons that "undo" the positive charge from the nucleus.

Ionization Energy

Ionization energy is the energy required to remove an electron from an atom in the gas phase.

It is always endothermic, since energy is needed by the system to move an electron away from the nucleus of the atom. However, simply the magnitude (or absolute value) of ionization energy is often discussed, to avoid confusion about what "larger" or "smaller" means.

The valence electrons in atoms of these elements are quite unfavorable, since they are either alone in the new p shell (Group 3A) or are one more than a half-filled p shell (Group 6A). Therefore, it is quite favorable to remove one valence electron.

Calculating ionization energy

In photoelectron spectroscopy, explained below, it is important to calculate the ionization energy for a photoelectron (an electron that escapes an atom after bombardment by a photon).

The ionization energy of a photoelectron can be calculated by subtracting the kinetic energy the photoelectron after it is expelled from the kinetic energy of the original photon, which provided the force. The energy lost was used to remove the electron from its atom.

Subsequent ionization energies

The second ionization energy (energy needed to remove a second valence electron) is always larger than the first ionization energy, and so on. This is because it requires more energy to remove an electron from an atom that is already positively charged.

If you see a large jump in ionization energies, that means that the next electron requires more energy to remove than usual. This indicates that, at this point, all electrons were removed from a sublevel and a new sublevel is being taken from.

For example: If you see a large jump between the energy required to remove the second and third electrons, removing the third electron requires breaking into a new sublevel. A possible configuration in this scenario is , since after the two 3p level electrons are removed, we need to dip into the 3s sublevel.

For example, 4s is removed before 3d.

Electron Affinity

Electron affinity is the energy change that occurs when an electron is added to a gaseous atom. The more negative (exothermic) the value, the greater the affinity.

In other words, electron affinity is the neutral atom's likelihood of gaining an electron.

Groups 2A and 5A have little interest in adding electrons, since they have good configurations by themselves (full or half-full p shells).

In Periods 1 and 2, the electrons are crowded so tightly together that making space for more electrons requires a lot of energy. Also, the existing tightly-packed electrons have a heavy repulsive force.

Properties of Metals

Alkali Metals

Alkali metals (Group 1A) are soft, metallic solids.

In nature, they are only found as compounds. They only need to lose one electron in order to reach a stable configuration, and therefore have very low ionization energy because they are trying to get rid of that electron. As a result, they react violently with water and air, trying to get rid of that extra electron.

Noble Gases

Noble gases (Group 8A) have large ionization energies — they have very stable configurations, so it takes a lot of energy to remove an electron. Therefore, they are relatively unreactive, and are found as monatomic gases.

Photoelectron Spectroscopy (PES)

Photoelectron spectroscopy allows scientists to determine the ionization energy of all electrons in an atom. In PES, a gaseous sample of atoms is bombarded by X-rays or ultraviolet light (photons) of known energy. The kinetic energies of the photoelectrons that are ejected from the atoms are measured. The number of photoelectrons with the same kinetic energies is noted. Although only one electron is removed from each atom, several atoms are ionized in the experiment. The electron that is removed will differ from atom to atom. The collective result provides information about all the electrons in an atom of the sample.

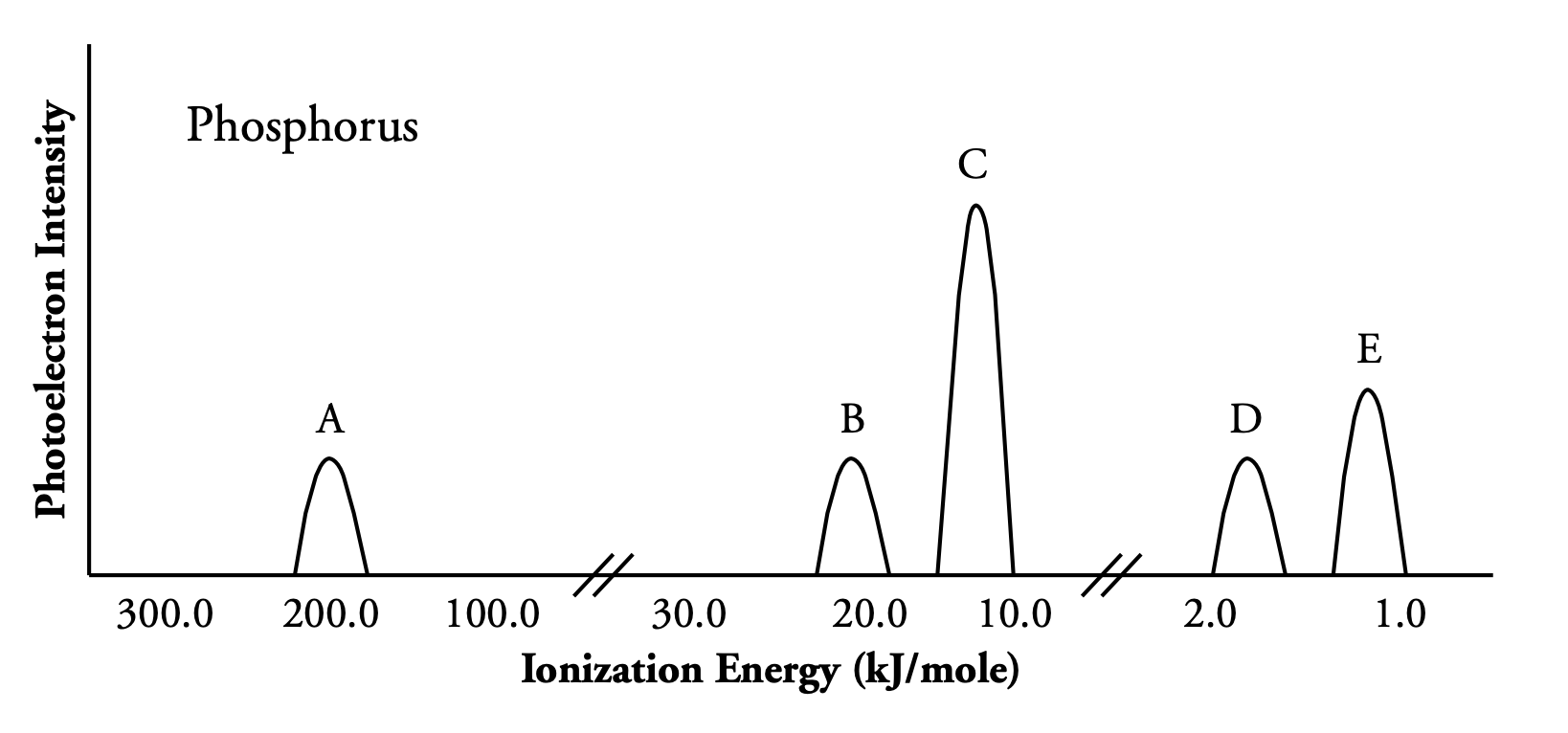

A PES spectrum looks like this:

The position on the x-axis of each peak represents the amount of energy needed to expel those photoelectrons, and the height of each peak represents the relative frequency with which these electrons exist in this element.

The shells closest to the nucleus have the highest ionization energies, so they are found towards the left side of this diagram.

By comparing the heights of these peaks, one can see that:

- A is

- B is

- C is

- D is

Therefore, peak E is shell . Since peak E is half the height of peak C, there are half as many electrons represented by peak E, so peak E has 3 electrons. This tells us that the element shown here ends with , so it's Phosphorus.